As Donald Trump begins his second term as president of the United States, the global rise of right-wing populism has never been more obvious or dangerous. As well as controlling the world’s most powerful government, right-wing populists rule, or are members of government coalitions, in seven European Union member states, including Italy and the Netherlands. They won a state election in Germany and provide critical backing for the Swedish government in parliament in exchange for a role in shaping its policy.

Far-right parties also form substantial political oppositions in France and Germany, and are increasingly influential in the United Kingdom; the far-right party, Reform UK, is rapidly rising in popularity, and there is strong right-wing populist influence within the Conservative party which left government last year. Much of their power is not only electoral, but in the influence they exert on the public discussion, framing issues and forcing governmental positions, as recently occurred with the UK grooming gangs debate.

Many see these shifts towards right-wing populism as isolated shocks - but they are in fact symptoms of deeper, interconnected forces that have been reshaping our economies, societies, and politics for decades. Understanding these forces is the first step in grasping why right-wing populism has surged and how we might respond.

This article was initially published by Iyad El-Baghdadi and Ahmed Gatnash in early 2016, on our platform The Arab Tyrant Manual, to reflect on the shocking first presidential victory of Donald Trump and track the origins of the rise of right-wing populism. We have decided to republish it, lightly edited, in the wake of his second inauguration 8 years later, in order to evaluate our analyses, reflect on how these dynamics have continued to play out, and encourage continued debate of the issue.

1 - The Triumph of Globalization

Before examining how globalization set the stage for today’s political upheaval, it is important to see it not just as a buzzword, but as a historic force that has reshaped economies, societies, and individual identities. Over the past few decades, global interconnections - through trade, technology, and migration - have accelerated at a pace that outstrips the ability of many institutions to adapt. This rapid change has sparked both remarkable economic growth in some regions and deep anxiety in others, fueling the discontent that right-wing populists have so effectively harnessed.

It is difficult to capture in a few lines the impact that globalization has had on our world. Our societies have had to contend with an inflow of new immigrants threatening a previous perceived homogeneity, new ideas threatening old traditions and customs, and new technologies disrupting old institutions.

In the words of Zygmunt Bauman - the Polish-born sociologist who examined changes in the nature of contemporary society - “what has been cut apart cannot be glued back together.” The pace and depth of change have been so dramatic, and many people feel not only left behind but that their settled sense of identity - formed during more ‘stable’ times - is being upended. While this dislocation is felt broadly, it is especially intense among the elderly white demographic who yearn for a past when their towns looked and sounded much like themselves, and when immigrants - particularly Muslims - were far less visible. A crisis of identity and an uncertainty as to what nations will look like in the future fuels much of right-wing populist sentiment today.

The anger against globalization is - in no small part - a reaction against its triumph and a testament to how profoundly it has changed our world. This change happened so swiftly that our social and political institutions have struggled to keep up, leading to the sense that nobody is in control. By tapping into resentment toward ‘outsiders’, promising a return to traditional American values, and framing globalization as an elite-driven threat, Trump has effectively channeled the anxieties of those who feel most displaced. Yet as we will see, these forces shaping the right-wing populist resurgence run far deeper than any single election - and point to the need for new ways of thinking about identity, belonging, and governance in a global age.

2 - The Loss of Anchors

The transformation that societies underwent, and the particular havoc that it has wreaked on the sense of identity, has served as the perfect fuel for rising worldwide identity politics.

Systems of belonging that had existed for centuries have eroded, or even disappeared. The meaning and structure of community - be it religious, national, or even the family - have transformed deeply. Societies went from extended families to nuclear families to the post-nuclear family, often in the space of no more than two generations.

In many places, new generations are growing up with values starkly different - and even directly contrasting - to those of their parents. This shift in values is perhaps most stark in the most insular societies, which modernity has crashed against in wave after wave over the past few decades - the American ‘bible belt’ for example, or the Arabian desert plateau of Najd in Saudi Arabia. What was ‘normal’ a generation ago, is today not only challenged, but often mocked.

Much of the conservative backlash that is expressed by religious fanatics, or the nativist backlash by ethnic hate groups, is at its core a reaction to this loss of traditional anchors. In times of fear and uncertainty, people tend to fall back on their group identity for security, and identity politics - with its emphasis on differences and otherness - lends itself more to exclusion than inclusion, and to authoritarian structures rather than open ones.

Let’s not go too far, though. This sense of uncertainty is widespread, but these ‘radicals’, who embrace what they perceive to be ‘traditional’ values and seek a return to an ‘authentic’ social state, stand out precisely because of the stark contrast against their own peers who seem to be comfortable in their own skin. Let’s not forget that, had the young had their way, then Trump would not have won, the Brexit vote would not have passed, and the 2011 popular uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) perhaps, would have succeeded.

3 - Economic Transformation

The economic transformation brought on by globalization has been deep. Some professions all but disappeared - others moved overseas - as economies became more interdependent and as a result, more specialized. In developing economies, embracing market reform and free trade has led to the greatest upward socioeconomic move in history - with billions no longer falling below the poverty line, many eventually found their way into a new middle class. This is most visible in large economies such as China and India, but can also be seen in Turkey, South-East Asia, and many African nations.

However, while poor countries caught up with the rich world, lifting millions out of poverty and onto the economic ladder, the divide between the richest and poorest individuals in the world increased. While billions of people outside of the West were no longer in poverty, billions of dollars flowed to fewer and fewer Western capitalists. As German economics professor Christian Kreiß renders it - so long we have compound interest and no cap on personal wealth, the end result will always be that more and more capital flows to fewer and fewer people.

The graph above shows that while everyone’s income grew, this growth was uneven. While the lower middle class in most developed economies are not worse off, it seems that everyone else has been doing far better. A demographic that was once confident in economic progress, and trusted that every new generation will do better than the previous one, now feels anxious about its future.

Those who had benefited from a previous economic order now see themselves as victims of change. For a time, the world seemed to be tailor fit for them - but now, they have to contend with an unfamiliar world that feels unfair and unsafe. Political leverage depends not upon absolute power but relative power. To the previously privileged, equality feels like a step down - and given the confluence of other trends and factors, the white working class voted with their ethnicity.

In 2014, Nick Hanauer, an American venture capitalist and a self-described “0.01 percenter”, gave a sinister warning; “If we don’t do something to fix the glaring inequities in this economy, the pitchforks are going to come for us”. On November 8th, 2016 - the day Trump won the US presidential race, we saw what that looks like.

4 - Obsolete Nationalism

Ethnic nationalism once energized and ordered the world. It championed a state model that emphasized the sovereignty of the ‘pure’ nation - went on to inspire millions - and to remould the world’s map. In the process, it precipitated countless disasters and gave rise to some of the most brutal totalitarian regimes of the last century. The modern populists are undoubtedly passionate ethnic nationalists. But the model of nationalism that they believe in - and the state model that it envisions, is obsolete.

It was always built on fantasies, but it did give the comfort of clear answers: Who ‘the people’ are, what their language, culture, and customs are, and what their origin was. But as our societies became more mixed, with citizens often hyphenating their identity - Somali-Norwegian, Pakistani-British, Algerian-French - the very reality of the pure ethnic state has eroded. Modern states today are no longer defined by an imagined ethnic homogeneity.

While ethnic nationalism as a system of belonging eroded, in many countries no alternative form of nationalism arose to replace it. It has long been acknowledged that a civic nationalism can arise, as an ‘open’ nationalism defined by membership in a society, emphasizing a shared destiny rather than an imagined shared origin. But the weight of history has made many countries slow to attempt to build it as a serious alternative.

Worst, our clinging to an obsolete vision of nationalism is contributing to an identity crisis among minorities, who feel a lack of belonging here or there. There is a limit to how much someone can assimilate, even if they want to - but there remains the question of whether it is humane or even desirable. Diversity is supposed to be a boon - but we are proceeding from an outdated concept of nationalism that sees it as a threat.

Identity - ‘who am I?’ - is among the deepest questions there is. In the absence of an effective system of belonging, individuals will not give up on identity. They will revert to the most familiar identity they know, regardless of its usefulness or appropriateness. Hence the swift retrograde to outdated nationalisms in an age where our societies are more diverse than ever.

Tragically, the one country which had offered arguably the greatest and most inspiring example of an open nationalism - the US - has elected into office a team of ethnic nationalists. And this has been, in no small part, a result of a political failure.

5 - Political Failure

The trends discussed so far have converged during a period of widespread political failure across the ideological spectrum. Although this failure looked different in the United States than in Europe, the underlying causes overlap.

In recent decades, politicians have shifted from principled leadership to a more managerial approach - tinkering at the edges of a system many believe has let them down. Take economics, for example: regardless of who was in power, the core structure scarcely changed. Adjustments in tax rates or differing rhetoric could not disguise the absence of a genuine vision for dealing with huge global shifts in the nature and structure of the economy. While some suspect a deliberate plot by elites to tighten their grip on power, it seems more likely that officials are simply muddling through without a clear plan.

Another root cause of this stagnation is the lack of innovative thinking. In many European democracies, parties converged on centrist positions, blurring meaningful distinctions between them. Where parties did not enact real policies, ‘ideology’ became an empty word - driving frustrated voters toward identity-based politics. This was especially damaging for the left, which abandoned many marginalized groups by moving to the center. Those who felt betrayed turned to far-right populism or religious extremism, depending on which identity resonated with them.

In the United States, these problems were even more acute. Rising polarization, the dominance of special interests, and a sense that politicians only cared about wealthy donors led many to see Washington as unresponsive and self-serving. ‘Career politician’ became an insult, and when people believe that politicians do not change anything, they become receptive to a combative, authoritarian, ‘outsider’ promising to “drain the swamp”. For many, Donald Trump was the “human Molotov cocktail” thrown at a system they felt had utterly failed them.

6 - Social Media Broke our Public Sphere

It is difficult to envision what globalization would be without the internet. It erased borders, democratized access to information, and undermined censorship by authoritarian regimes. But then came social media.

The “public sphere” is the social domain in which public opinion is formed - it is essential to the health of a democracy, and must be inclusive, representative, and marked by a respect for rational argument. As early as 2006, Jurgen Habermas - the world’s leading thinker on the public sphere - weighed in on what the internet would mean for democracy, expressing two primary concerns. First, the fragmented nature of discussions online - instead of having a single public sphere, the result is several non-overlapping ones. Second, the democratization of expression will increase the need for ‘quality press’ to ensure participants in the public sphere are well-informed.

When people can choose who to connect with - or not - they tend to connect with accounts that share views similar to theirs. Even those with an appetite for engaging with different opinions face the challenge of algorithms promoting content that tends to align with their views. Social media is, by design, built to allow people to find ‘filter bubbles’ - pockets of the internet that reverberate with sameness. ‘Filter bubbles’ worsen polarization, allowing people to exist in online echo chambers, accessing only opinions that validate rather than challenge them.

In recent years, as much of the early romanticism around social media faded, it has emerged that the impact it has had on social stability, the ability to have constructive conversations, and the sharing of information has been nothing short of catastrophic. Large-scale disinformation, whether produced by small profit-motivated actors, radicalized groups or political actors - including nation-state propagandists - has inundated most social media platforms. Platforms have been weaponized by democracies and autocracies alike to manipulate the public, sow social discord, or identify and hunt down dissidents. The platform ownerships have either declined to address these issues, failed in their efforts, or actively participated in and facilitated the decline.

In an era where disinformation is ubiquitous, the role of robust and high-quality journalism is arguably more important than ever, but its fate has not been a pretty picture. The newspaper industry initially benefited greatly from the rise of the internet - until social media and search engines changed the rules of the game. By giving marketers a clearly superior advertising tool, search engines and social media led to an enormous loss of advertising revenue for news media.

The internet gave news establishments wider distribution than ever before - but it also cut off their income source, and the industry still hasn’t found a viable alternative - real journalism is often paywalled, whereas disinformation is free. Underlying this problem is a deficient business model in the news media industry, and until that is fixed our public sphere will continue to suffer.

It is tragically ironic how the greatest democratization of expression in history led to the breakage of our public sphere – and it just happens that a failing public sphere has a symbiotic relationship with demagogues: Desperate news establishments, in their search for viewership to retain revenue, seek outrage and promote demagogues, subsidising the reach of their message to the masses.

7 - The Unravelling of the Middle East

With so many powerful trends tugging at it, the world order was bound to tear. And it tore first, fastest, and deepest in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

For decades, 2011 will be seen as a pivotal year in the region’s modern history. A year earlier, the MENA world order seemed largely stable, with complex but largely predictable power dynamics. Then 2011 happened.

The region’s youth shook their regimes in 2011, but by 2013 were left to their own fate as two counter-revolutionary axes tried to roll back the tide - one led by the Saudi regime and some Gulf states, and another led by the Iranian regime and its regional allies. But in their attempts to fight back against change, they only managed to break the region.

The 2011 popular uprisings were an enormous wasted opportunity - had they had a soft landing, they would have led to a new stability based upon wider popular consent, and perhaps a period of strong economic growth that would have benefited the West’s ailing economies.

The Syrian civil war was particularly catastrophic - it gave rise to ISIS, caused an enormous wave of refugees, and exposed a global political failure. Opportunistic players such as Putin’s Russia found the perfect conflict to exploit to destroy the “liberal world order” - cynically and skilfully using it to erode international norms in the name of “fighting terrorism”. Putin couldn’t throw missiles at Europe - so he threw waves of Syrian refugees at them.

Can we realistically separate the resurgence of authoritarianism in the West from the unravelling of the Middle East? The issues of refugees and terrorism have been among the greatest factors feeding support for the new populists.

The 2011 popular uprisings had represented a confluence of undercurrents, many of which were more global than “Arab” - demographic maturation, communications globalization, economic inequality, failing regimes, an ossified political elite, a misguided “war on terror”, a lack of global leadership, and an outdated foreign policy paradigm. The story of its failure captures all these trends combined.

Conclusion: The Trump Effect

The right wing populists want to solve intractable problems through exercising and asserting the sovereignty of the state (in their imagination, a “pure” state for a homogeneous people). But this is fantasy. You cannot apply nation-state scale solutions to global-scale problems. The challenges we face - terrorism, migration, the economy, climate change - are intractable precisely because they are global in nature, and hence beyond the ability of any individual “sovereign” state to fix. Neither can you “unmix” our societies after generations of immigration and intermixing. That imaginary “pure” nation-state to which they want to return is gone forever.

They seem to be standing within a broken paradigm, promising to rebuild it. But it is long shattered. If we are to borrow from Thomas Kuhn on the subject of paradigms, then the breakage of one only predicts the rise of a better one. Our world today is riddled with broken paradigms - of which the trends we described above are only a reflection. But we cannot go forward by going backward.

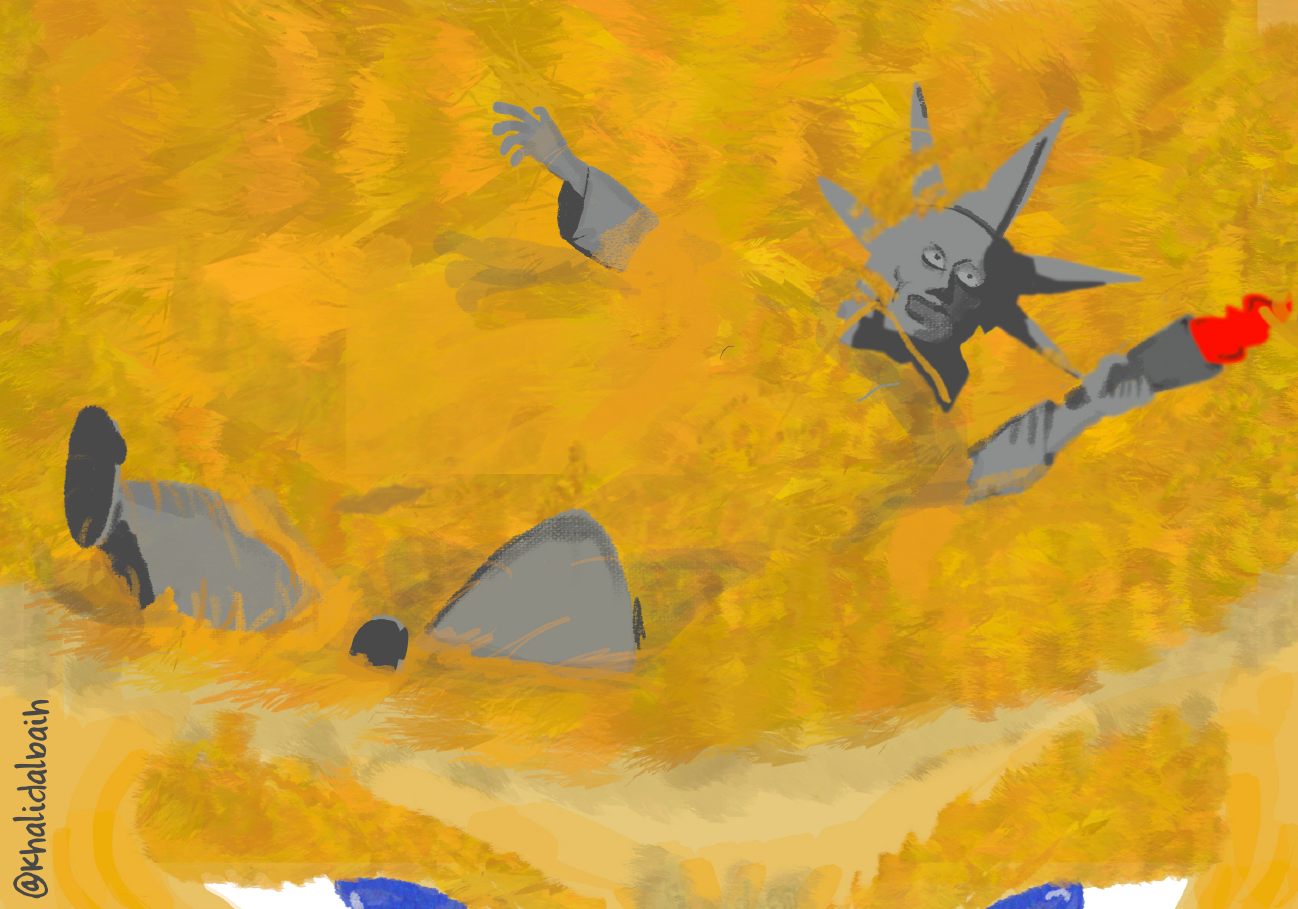

We happen to be stuck in the limbo between the breakage of an old paradigm and the rise of a new one. We aren’t witnessing the return of the paradigm championed by right wing populists - we are witnessing its death. In the words of Antonio Gramsci, “The old world is dying away, and the new world struggles to come forth. Now is the time of monsters”.

And monsters do not die quietly.

Iyad is co-founder of Kawaakibi Foundation and author of The Middle East Crisis Factory.